It has been suggested that some patterns of religious involvement in the USA are about 20 years behind those in Australia. The decline in church attendance which has affected mainstream churches in Australia over a period of 40 years is now having a significant impact on mainstream churches in the USA. Americans are now embracing the more individualised spirituality that is common in Australia and Europe, but with their own American twist. This is the story that American author, Diana Butler-Bass, tells in her book Christianity After Religion, and embraces as a new spiritual awakening!

Diana Butler-Bass is a well-known speaker and author and has visited Australia on speaking tours. She does little primary research herself but, for the most part, understands the research and draws on it well, along with numerous personal anecdotes. Her material is readable and insightful. While much that she describes as historical trends in the USA applies, or has applied, to Australia, the way that religious faith interacts with the culture is certainly a little different in Australia. Nevertheless, her thesis that there is a possibility of ‘Christianity after religion’ is worthy of attention.

Recent Changes in Attitudes to Religion and Spirituality

Butler-Bass begins her book by noting some of the major changes that have occurred in religion in the USA since the 1970s. On 4 April 2009, the cover of Newsweek announced ‘The End of Christian America’. Its evidence was that between 1990 and 2009, the proportion of Americans identifying as Christian dropped from 86 to 76 per cent and the percentage unaffiliated with any particular faith rose to 16 per cent. Butler-Bass notes that many clergy are saying that attendance at religious services is significantly down and even belief in God has eroded (p.16). Butler-Bass suggests that people are bored with, and sometimes angry, with religion. Many people are simply saying that institutional religion is irrelevant to their lives. She tells of people who move from one church to another, failing to find a place where the deeds match the words and where the values reflect their understanding of Jesus’ values (p. 24).

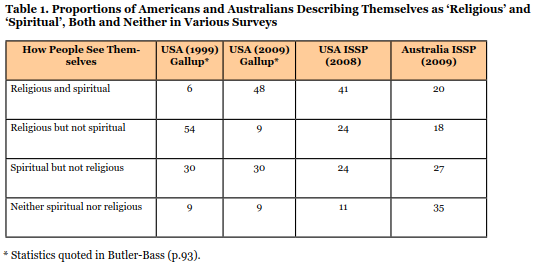

The major shift in the USA has been in the proportion considering themselves ‘religious but not spiritual’ down from 54 per cent in 1999 to 9 per cent in 2009. The proportion describing themselves as ‘religious and spiritual’ rose from 6 per cent to 48 per cent.

According to Butler-Bass, the reason for the significant movement in relation to ‘religion’ is disillusionment with religious institutions. She notes a range of events in the first decade of the 21st century which have contributed to this. Some of these events have also had an impact on Australian attitudes.

2001. The September 11 terrorist attacks.

Over time, this was seen as the result, not just of a certain form of Islamic extremism, but of general religious fanaticism and fundamentalist zealots. The mood was picked up by Christopher Hitchens who wrote:

People of faith are in their different ways planning your and my destruction, and the destruction of

all hard-won human attainments [art, literature, philosophy, ethics and science]. Religion poisons

everything. (p.77. Quoted from Hitchens 2007)

Terrorism has also rocked the faith of many Australians. There is a widespread belief that taking religion – any kind of religion – too seriously is dangerous. The Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (2009) found that 75 per cent of Australian adults believe that religion contributes more to conflict than to peace.

2002. The Roman Catholic sex abuse scandal.

The scandal in Boston broke in the public media in 2002 with accusations of five priests sexually abusing children. Butler-Bass quotes a Pew survey that indicated that one-third of all Americans raised as Catholic no longer identify themselves as Catholic. The problem, however, has had an impact well beyond the Catholic church with a decline in confidence in clergy generally (p.78).

The decline in confidence in the clergy and in the religious institutions has also occurred in Australia. In 2001, the International Social Survey Program found that 34 per cent of the population had much or complete confidence in the churches and religious organisations. In 2009, 22 per cent of the population had this level of confidence (Hughes and Fraser 2014, p. 116). It is very likely that sex abuse scandals have contributed to this decline in confidence. For some people, they have been ‘proof’ of the hypocrisy of some Christians. While people will acknowledge that sexual abuse has occurred in non-religious setting, the fact that the churches have claimed to be the guardians of morality has exacerbated the hypocrisy in the eyes of many people. The cover-up in some church structures has demonstrated how some church officials have been more interested in preserving the reputation of their organisations than the well-being of people.

2003. Protestant conflict over homosexuality.

The conflict that arose over the appointment of Gene Robinson as an archbishop in the Episcopalian Church of the USA brought the issue to a head. Butler-Bass argues that it was not just the issue of homosexuality itself, but the nastiness with which the battle was fought among religious people that did most damage to the reputation of the churches. She suggests that it lead to many people thinking of churches as making people mean, bigoted and behave badly (p.80).

While there has been conflict in the mainstream churches in Australia over homosexuality, it is likely that the public concern has not been over the ‘nastiness of the battle’, but over the perception that many churches do not accept people in homosexual relationships. It is an example, in the minds of some Australians, of judgemental attitudes within the churches.

2004. The religious Right wins the battle, and loses the war.

In 2004, George W. Bush was elected president of the USA. This was widely seen as the greatest victory in USA politics of conservative evangelicals. However, Butler-Bass argues that this event ended in the alienation of a whole generation of younger evangelical people who felt that what George Bush did in government was contrary to their Christian ideals. The religious Right was seen by many people as ‘anti-homosexual, judgemental, hypocritical, out of touch with reality, overly politicized, insensitive, exclusive, and dull’, Butler-Bass says (p.81).

In Australia, the cultural wars have not played out in politics in the same way as in the USA. While there were some attempts by the Howard government to court the Pentecostal vote, the interplay between religion and politics has been small and not highly significant in Australia.

2007. The Great Religious Recession.

Butler-Bass argues that the economic crisis occurred when religions were already in recession. But the economic recession further weakened religious organisations and contributed to people seeing them as irrelevant to their struggles in life (p.82). As Australia has not had the same depth of economic recession, it has not had a parallel religious recession.

Butler-Bass suggests that, just as the two-party system of American politics has become ‘bogged down in issues, styles, and practices of the past, so too American religion is stuck in issues, styles, and practices of the past’ (p.85). Many people simply opt out. They are no longer interested.

However, this discontent, Butler-Bass suggests, is fueling the interest in ‘religion and spirituality’. There is a new attention to ‘experiential Christian life’ (p.93). While Butler-Bass acknowledges that religion may give way to secularism in Europe and Australia (p.95), she thinks that it may lead to a transformation and renewal of religion in America (p.96). Religion as a system of belief will be replaced by a way of living, and of seeing and feeling the world, something more experiential (p.97).

In Australia, there has been a steady growth of interest in spirituality since the 1970s. Since 2000 there has been a marked decline in confidence in the churches and religious organisations and this has a significant relationship with the extent of belief in God among Australians (Hughes 2012). Butler-Bass is partially correct in that some of the decline in confidence in the churches is giving way to secularism. However, that decline is also contributing to growth in the affirmation of ‘spirituality without religion’. It is not leading to a growth in the affirmation of ‘religion and spirituality’ that Butler-Bass reports in the USA.

A New Awakening

Butler-Bass suggests that the underlying change is a new ‘Awakening’ with similarities to other religious awakenings that have occurred in American history. She outlines the transformation that is occurring under three major headings: believing, belonging and behaving.

Believing

Belief, she suggests, has meant accepting certain ideas about God and Jesus, especially as expressed in the creeds of the church. She suggests that Christianity is moving, or rather, re-discovering, that it is not a religion about God, but rather an experience of God. The question changes from what I believe to how I believe. It is a shift from the question of information to that of experience and connection (p.113). It is also a question of who I believe: a question of relationship, authority and trust. Belief, then, is like a marriage vow, Butler-Bass says, ‘a pledge of faithfulness and loving service to and with the other’ (p.117).

Butler-Bass takes up the question of one her correspondents on Facebook, ‘Why is it that the choice among churches always seems to be the choice between intelligence on ice and ignorance on fire?’ (p.121). In response, she calls for ‘a new wholeness of experience and reason’ (p.127). Following Parker Palmer, she suggests that the heart can integrate our various ways of knowing, including through reason and experience.

Behaving

Butler-Bass suggests that we used to learn how to behave religiously by copying the behaviour of our parents and through joining in the community of faith. Today, in a world where we develop our own patterns of life which are often very different from those of our parents, she suggests people are developing intentional religious practices. These may be specific times of prayer or fasting, of keeping a day of rest or offering hospitality to strangers (p.146).

She notes that people often mix practices from different sources and suggests that this signifies ‘a renewal of spiritual imagination and creativity’ (p.150). People will not take on practices as a matter of duty and obligation as they have done in the past, but as intentional ways of imitating Jesus and the saints and those whom we admire (p.155). They become ways of anticipating the realities of God’s Kingdom in the world, she says (p.159). ‘Spiritual practices are living pictures of God’s intentions for a world of love and justice’ (p.160).

Belonging

As the old categories of belonging no longer resonate well with us, the emerging answer to the question ‘Who am I?’, Butler-Bass suggests is ‘I am my journey’. She suggests that much of the Scripture is about spiritual journeys. However, she goes on to say that we find our identity in God and in finding that God is in each and every person. She adds the idea that we exist through God. As a movement preposition, ‘through’ reminds us that we are not static.

Through God new possibilities open for growth as we move beyond our perceived limitations to new

strengths, insights, and compassion. … Christian spirituality of the self enjoins that God is not only

located in us, but that God acts, speaks, heals, loves, touches, and celebrates through us (p. 191).

She notes that people shy away from ‘I am a Presbyterian’ and prefer to say ‘I go to a Presbyterian church’. She notes that the ‘Presbyterian church’ is no longer a static or inherited identity. Indeed, she says, ‘church is no longer membership in an institution, but a journey toward the possibility of a relationship with people, a community, a tradition, a sacred space, and, of course, God’ (p.192). She notes that Christian spirituality is not individualistic but communal and relational.

The Order: Belonging, Behaving, then Believing

Butler-Bass notes that, in the past, Western Christians have ordered faith in terms of belief first, then behaviour and finally belonging (p.201). People expected that there would first be a commitment of belief, by parents for their children if not by the children themselves. Then those who had made the commitment of belief would learn the right behaviour. Finally, they would be accepted into the community, for example, through the rite of Confirmation. She argues that Jesus’ pattern was to begin with ‘belonging’: the forming of community (p.203). That led to becoming involved in the practices of the community as the company of disciples healed people, offered hospitality, prayed

together, fasted and forgave (p.207). Finally, they began to see things differently. The confession of faith grows out of the relational community and the things people have done together (p.208).

The History of the Awakening

Towards the end of her book, Butler-Bass goes back to the changes that took place in the 1960s and 1970s: the new religious practices and communities, the new theologies of liberation, the Jesus people, the charismatic movement and Christian feminism. She argues that this was the start of an ‘Awakening’ (p.219). It was a time when people attempted to change their lives, communities and the world in accord with God’s love and justice, she says (p.221). ‘Awakenings are movements of cultural revitalization that “eventuate in basic restructurings of our institutions and redefinitions of our social goals” (p.28), says Butler-Bass. Awakenings usually occur through breakdown and decline, followed by a time of re-imagination and possibility, then finally a time of reform of institutions and social change (p.34).

Butler-Bass compares the current changes with the previous three periods in American history of

intense religious revitalisation:

• 1730-60 prior to the American Revolution;

• 1800-30 in the early decades of America as a republic; and

• 1890-1920 as the United States became an industrial nation (p.221).

She argues that the 1960s was the beginning of the Fourth Great Awakening. However, Butler-Bass suggests that there was a backlash which was symbolised in the election of Reagan and in the rise of Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Jim Bakker and other conservative religious leaders which stunted the spiritual revitalisation (p.228). This backlash saw people turning back to ‘old-time religion’ and towards an absolutist, sin-hating, death-dealing God (p.228) playing to people’s fear of women, Islam, pluralism, environmentalism and homosexuality (p.231). However, she says that this ‘boom’ of dogmatic religion was over by the 1990s (p.235).

In each of the Awakenings, Butler-Bass argues that ‘romantic elements of religion’ such as adventure, quest, mysticism, intuition, wonder, experience, nature, unity, historical imagination, art and music, come to the fore (p.236) and formalised dogmatism and institutional authority are repressed. So, she suggests, the Fourth Great Awakening is challenging ‘ failed institutions, scarred landscapes, wearied religions, a wounded planet’ (p.238). She suggests that one dimension of this Great Awakening is that it is ‘interfaith’ and involves, not a rejection of distinctives, but a learning to live with particular faiths while ‘honoring the wisdom of others in a mutual, spiritual quest toward “full human existence”’ (p.243). Indeed, Butler-Bass suggests that there are parallel Awakenings in Buddhist, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim and Hindu societies emphasising renewed attention to the spiritual dimensions of their traditions, communal identity, faith practices and experiential belief (p.244). Indeed, she suggests that such Awakenings are sweeping across the globe in this ‘Age of the Spirit’ (p.245).

There continue to be reactionary movements which attempt to shut down the Awakening, such as the Tea Party (p.248) in which authority and conformity are offered as the ways to health, happiness and salvation. She notes that history is full of ‘fear-filled, backward looking, violent believers’ (p.249). However, ‘fear-filled religions stand in sharp contrast to compassion-based spiritual awakenings’ she suggests (p.249) and the real struggle is not between different religions but within religions, between those who are looking to creating a new future and those are trying to halt it (p.249).

How do people participate in this new Awakening? Butler-Bass says there is no specific technique and no set program to follow. ‘If you want it to happen, you just have to do it. You have to perform its wisdom, live into its hope, and ‘act as if’ the awakening is fully realised. And you have to do it with others in actions of mutual creation.’ (p.262). She concludes:

This awakening will not be the last in human history, but it is our awakening. It is up to us to move with the Spirit instead of against it, to participate in making our world more humane, just and loving (p.269).

An Australian Awakening?

Whether there is an ‘Awakening’ in the United States, or whether the cultural changes that are occurring lead to a secular approach to life remains to be seen. There appears to be a basic ambiguity in the account of Butler-Bass. She describes people as losing confidence in the churches and ceasing to belong to them, and yet, at the same time points to people continuing to describe themselves as both ‘religious’ and ‘spiritual’. One would expect that the loss of confidence in the churches and in institutional forms of religion and the declining involvement in churches would lead to a weakening of Americans’ self-description as ‘religious’. In other words, the long-term movement could be into ‘spirituality without religion’ rather than ‘religion and spirituality’. It could lead not to ‘Christianity after religion’ as in Butler-Bass’ title of her book, but to a ‘spirituality after religion’ which sees itself as distinct from the Christian tradition.

Many of the expressions that Butler-Bass associates with an Awakening are occuring in Australia, but quite outside the churches, such as the sense of the unity of humanity, the need for social justice, the importance of art and music, the concern for the planet and the recognition of intuition, experience and mystery. In some parts of Australia, there is greater openness to the multiplicity of religions as part of multiculturalism. However, as part of that, there is widespread rejection of religious organisations and anything that approaches dogmatism in religion or religious extremism. Many people in Australia would not describe this new spiritual ethos as ‘Christian’. While close to half of all Australians consider themselves as not having religion and as not being spiritual, there has been an increasing proportion open to ‘spirituality without religion’ and, for many of those people, the spiritual is essentially Christian.

The challenge for the chuches in Australia and also in the United States is whether they can take on board the new spirituality sufficiently to connect with the population. Can they find different ways of offering meaning, nurture and a sense of community, perhaps through quite different structures from those which now exist? Or will an ‘Awakening’ in Australia, and perhaps also in the United States, pass the churches by?

Philip Hughes

References:

All references in this article are to D. Butler-Bass unless otherwise stated.

Butler-Bass, D. (2012) Christianity After Religion: The End of Church and the Birth of a New Spiritual

Awakening, New York: HarperCollins.

Hitchens, C. (2007) God is Not Great, New York: Hachette.

Hughes, P. (2012) ‘Belief in God: Is the ‘New Atheism’ Influencing Australians?’ Pointers, Vol. 22,

no. 1, March. pp.1-7.

Hughes, P. and L. Fraser (2014) Life, Ethics and Faith in Australian Society: Facts and Figures, Melbourne: Christian Research Association.

This article was first published in Pointers: the Quarterly Bulletin of the Christian Research Association, vol. 24, no.4, December 2014. pp. 5-9.