A recent book by Rodney Stark, a renowned sociologist of religion in the United States of America, America’s Blessings, argued that church attenders, on average, have an expectation of 7.6 years of life longer when they are 20 years of age than do non-church attenders (Stark 2012, loc. 1554). He argues that part of it is due to the ‘clean living’ of religious people. However, over and above that, he maintains religion contributes to lower blood pressure. In addition, he quotes another large study which found that church attenders were less likely than non-church-attenders to have strokes. The major reasons, the book suggests, for these positive relationships are the fact that religion allays anxiety and tensions, loneliness and depression, and that it provides social support (Stark 2012, loc 1575). The data from a survey of public health which is part of the International Social Survey Program allows us to make some examination of the relationship between religious faith and health among Australians.

Factors in Public Health

Health is not easy to define. A widely accepted definition of health that was used in the constitution of the World Health Organisation in 1946 is ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity’ (AIHW 2014, p.3). In other words, health includes mental and social dimensions and is not simply a matter of physical ability or the functioning of the human body.

One’s health is influenced by a great many factors, from our genetic make-up and our behaviour to our social interactions. It is influenced by viruses and bacteria that interact with us. Accidents which cause physical hurt also have an influence on our health. To varying extents, some of these factors are outside the individual’s control.

At the international level, the most important factors in the levels of public health include unsafe water and lack of sanitation which increase the risk of the transmission of diarrhoeal diseases, trachoma and hepatitis. The use of solid fuels in the household generally increases problems with pneumonia and other respiratory diseases (World Health Statistics 2013, p.109). However, these are not major issues in most parts of Australia. In Australia, as in many Western countries, the major positive influence, often referred to as a protective factor, in health is a high daily intake of fruit and vegetables. The major negative factors, or factors which increase risk, include tobacco use, physical inactivity and the harmful use of alcohol (AIHW 2014, p.17).

In more general terms, our health is influenced by our involvement in society, our knowledge and beliefs, our education, employment, income and wealth, housing, family and neighbourhood (AIHW 2014, p.18). Our psychological state can have a significant impact on our physical health. Stress, trauma and depression can all contribute to physical ailments. How might religion play a role in health? There are several possible ways. The first is that religion might motivate people to behave in ways which minimise risks to health. The general teaching of religion that one should take care of one’s physical body might motivate people to eat healthily, to take regular exercise, and avoid practices which reduce health, such as smoking and drinking alcohol immoderately.

Secondly, religions generally contribute to a sense of hope and purpose. They provide comfort in the face of disappointment and tragedy (Stark 2012, loc.1552). The Abrahamic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam do this by teaching that people are part of a world that has been created by God, and that each individual has a place in that world. The Eastern religions of Hinduism and Buddhism also provide a view of the world and of the individual’s place in it and ways in which the individual may, over many life-times, reach higher statuses within that world. More specifically, most religions teach that there is help available from God or saints through prayer.

A third way in which religions may support people is through religious communities. Religious communities reinforce a sense of belonging: the belief that each individual has a place and is of value. They can also provide support in practical ways, especially during the challenging times of life. Within the religious community, there will often be people with whom to share one’s problems. Sometimes, there are people within the religious community who are able to offer practical assistance in such forms as meals or advice.

The Research Methods

The International Social Survey Program (ISSP) 2011 on public health allows some testing of these hypotheses in relation to Australians. One of the limitations is that the survey contains very few questions on religion. There are no questions on religious up-bringing or exposure to religious communities when the respondent was a young person. There is also nothing about the form of religious involvement or the expectations of the religious group in which the person is involved.

There is one question on religious identity, but it is well-known that many people are not involved in the religious communities with which they identify. There is also one question about the frequency of attendance at religious services. On the basis that attendance at religious services at least monthly suggests some form of commitment to a religious organisation, some exposure to its teachings, and a likelihood of being influenced through a religious community, this is taken as a rough indicator of a person having some religious involvement and being open to religious influences.

Another limitation of this survey is that one is reliant on people reporting their health, rather than actually measuring levels of physical and mental wellbeing objectively. The ISSP survey measures health by asking, how frequently in the past four weeks, the respondent had:

• health problems,

• had bodily aches and pains,

• felt unhappy and depressed,

• lost confidence, and

• did not overcome those problems.

There was also a general question on the respondent’s health status, measured from ‘poor’ to ‘excellent’. These six items related strongly.

Five Factors in Health

A preliminary examination of the social variables in the ISSP (2011) survey shows that there are five significant factors in the level of health:

• whether one is employed,

• one’s level of education,

• age,

• gender, and

• and whether one is living in a steady partnership.

People who are employed or in training, highly educated, and in a steady partnership are more likely to have a high level of health. Age is significant, although not as significant as employment status and education. Women report more health problems, although this may be partly the cultural tendency among Australian men not to acknowledge health problems, especially on a self-reporting survey. These five factors, together, account for 6 per cent of the variance in reported level of health. As previously noted, much of the variance in health is a result of personal genetic factors, and the particular interactions one has with viruses and bacteria.

The survey enables us to look at what difference behavioural factors make to the reported health status. The most important factor, eclipsing all other factors, is how often one eats fresh fruit and vegetables. A second factor is whether one has frequent physical activity.

The impact of smoking and drinking on health is complex. Sometimes people smoke for a considerable length of time before it has a major impact on health. In general, however, people who reported smoking more were more likely to report that their health was not as good.

According to the results in the survey, the moderate drinking of alcohol had no measurable impact on health. Those who reported drinking several times a week reported better health than those who had never drank alcohol. However, those few who were drinking alcohol on a daily basis reported a significantly higher level of ill-health.

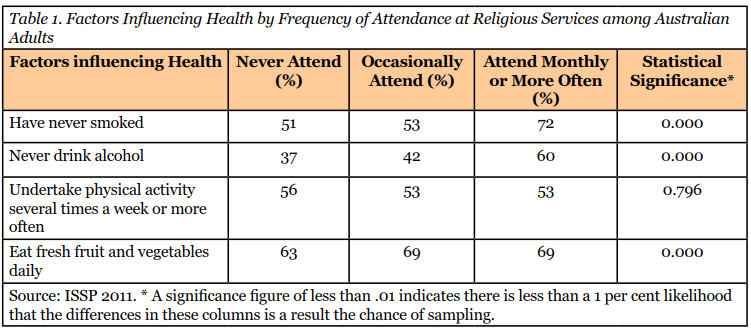

Does the evidence show that attendance at religious services makes a difference to health? Table 1 shows that 72 per cent of people who attend religious services monthly or more often have never smoked compared with 51 per cent of people who never attend religious services. There is a similar difference in regards to drinking alcohol. The statistical significance figure shows that these differences are very likely to apply to the whole population. However, the difference in the frequency with which religious attenders and non-religious attenders engaged in physical activity was not statistically significant. The difference in the frequency of eating fresh fruit and vegetables was no different whether one attended religious services occasionally or frequently.

Different denominations have different expectations in regards to smoking and drinking. The Seventh-day Adventists do not permit their members to either smoke nor drink and do encourage vegetarian diets. Many Baptists and people with a Methodist background have been teetotallers, although the expectations that they would not drink at all has weakened in recent decades. Most Catholics and Anglicans drink alcohol. However, most religious groups have never developed strong expectations about undertaking physical activity or eating fresh fruit and vegetables.

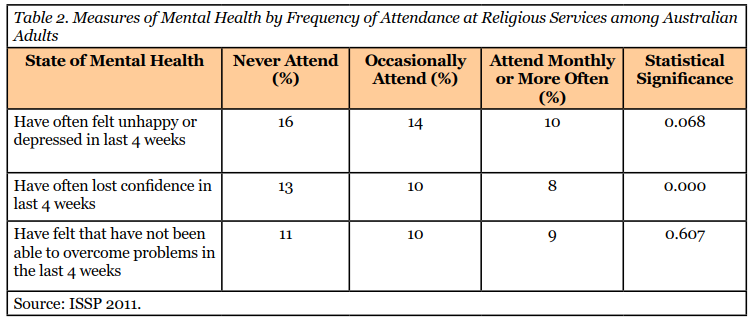

As has been mentioned, there are reasons to expect that religious attenders may have less depression than people who do not attend religious services, partly because of the sense of hope and comfort in religious beliefs and partly because of the involvement in and support from religious communities. Table 2 presents the findings using the rough measures of self-reports of feeling unhappy, losing confidence and not being able to overcome problems.

The differences between those who never attend religious services and those who attend frequently, as shown in Table 2, are relatively small. However, taking them together, they do indicate that there is a slightly tendency for people who attend religious services frequently to report fewer symptoms of poor mental health than those who never attend.

Another rough measure of health which avoids a purely subjective response is to ask people how often they had visited a doctor or visited an alternative healthcare practitioner in the past 12 months, and whether, in that period of time, they had been in hospital as a patient overnight. While it gives us another perspective on people’s level of health, it is also an inaccurate measure in that people vary considerably in the level of sickness which will lead to them visiting a doctor. Many healthy people also visit doctors for regular check-ups.

The survey found that:

• 23% of those who never attended religious services had visited a doctor often or very often, compared with

• 18% of those who attended occasionally, and

• 24% of those who attended monthly or more often.

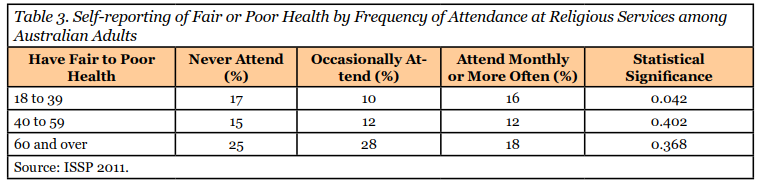

Thus, occasional attenders were using the health services least. The differences were statistically significant. One might expect that older people have more health problems than younger people, and religious attenders are generally older than non-religious attenders. Hence, it is necessary to take age into account. Table 3 shows the differences in both age and frequency of attendance at religious services in reporting their health as fair or poor.

Table 3 shows that there was little difference in the health among younger people (18 to 39 years old) between those who never attended religious services and those who attended monthly or more often. Those who attended occasionally had better health. While older attenders reported more frequently that they had fair or poor health, the differences with those who occasionally or never attended religious services were not statistically significant.

Other measures demonstrate similar findings. More religious attenders than occasional or non-attenders under the age of 40 reported they had had health problems in the last four weeks and that they had often had bodily aches and pains. Twenty per cent of them reported they had visited a doctor often or very often in the last 12 months, compared with 22 per cent of those who never attended religious services, and just 17 per cent of those who attended occasionally. Occasional young attenders reported significantly higher levels of health.

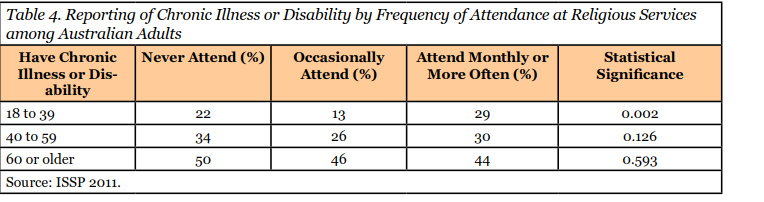

Part of the reason for these results can be found in Table 4. It shows that, particularly among younger people, there are more people with long-standing illnesses, chronic conditions or disabilities attending religious services. Indeed, nearly 30 per cent of all younger attenders indicated they had a chronic illness or disability, compared with just 13 per cent who attend occasionally.

It seems likely, then, that people, and particularly younger people, with chronic illnesses and disabilities, are more likely than other people to look to religious communities for support and have high levels of involvement. The fact that this is most notable among younger people suggests that this may be happening more than in the past. Or perhaps, over the years, more of the people with disabilities or chronic illnesses cease religious involvement. That cannot be determined from this data.

It remains possible that religious teaching and community does have an impact on health. One would probably need a complex longitudinal study of large numbers of people to prove that it does have an impact. If more people with poor health are attracted to the religious groups, one would need to follow such people over a period of time and see how their health fared compared with another group of people with similar levels of health who did not have any religious involvements. While there are some reasons to think that religion may have an impact, the cross-sectional statistics from this survey would indicate that the most healthy people are those who attend religious services occasionally.

However, we know that there are significant differences between those people who attend religious services and those who do not. Those who attend services tend to be older and better educated. Women attend more frequently than men. People with manual occupations attend less frequently than those with professional occupations. The ISSP 2011 survey enables us to examine the impact of religion on public health, controlling for a range of these other factors.

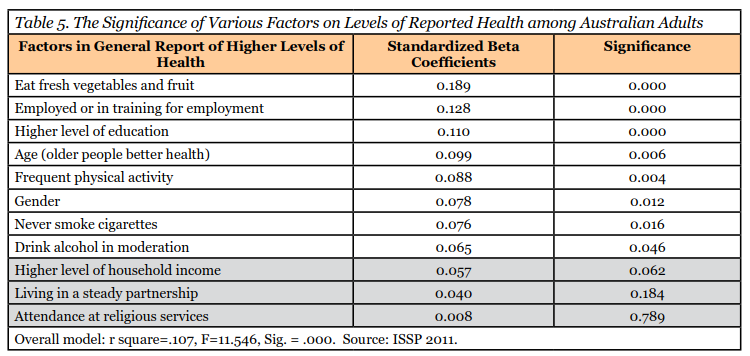

Table 5 sets out the ‘beta coefficients’ from regression analysis for the various factors and shows the level of impact of the particular factor when taking into account all the other factors. The factors have been arranged in order of size. If the significance level of a factor is above .050, then there is more than 5 per cent chance that the factor is just a result of chance and it would generally be said that that item does not have a statistically significant relationship with the level of reported health (in the grey area of the table). Hence, attendance at religious services, living in a steady partnership and the level of household income are not significant in this model.

Conclusions

Apart from eating fresh vegetables and fruit, the two factors that are most important in higher levels of health are employment and education. In some ways, these may have impacts similar to involvement in a religious community. Education is probably associated with people having better information about health and the risk factors related to health. Employment provides a community which is often experienced as supportive and through which people feel that they are making a contribution to something bigger than themselves. In other words, it is quite possible that, within the Australian community, people who do not attend churches find other communities which give them meaning and support in their lives.

A study of the relationship between public health and religion in 2002 found similar results. While it did not control for education, it controlled for age and gender. It found weak relationships between health and whether one took a religious, spiritual or non-religious approach to life. Indeed, the survey found that those who took an uncritical approach to religious faith, as distinct from a reflective approach, reported lower levels of health. Again, the study noted that one of the major factors in health is exercise and religious people do not exercise more than non-religious people (Kaldor, Hughes and Black 2010, pp.77-79).

However, it is possible that the insignificant relation between religion and public health may partly reflect the fact that some people with poor health are drawn to religious communities because of the personal support these communities provide, and a longitudinal study would determine that.

While it is beyond the scope of this article to examine the relationship between religion and health in various countries, it can be noted that this survey does show that the relationship between health and religious attendance does vary from one country to another. Taken across the forty-four countries where the survey was conducted, there was no difference in health level between those who attend religious services monthly, occasionally and never. However, in the United States, those who attended religious services monthly reported a higher level of health than did those who never attended. Why these differences exist needs much further exploration. The difference that religion makes to health in different countries is indicative that different groups of people attend religious services in different cultural and social contexts.

Theologically, it is sometimes argued that Christians have a responsibility to care for the physical body as ‘a temple of the Holy Spirit’ (I Corinthians 6.19). While this argument is used by the Apostle Paul to refrain generally from sexual immorality, and prostitution in particular, it has also been used as a basis for not taking illicit drugs and for looking after one’s physical health. A contemporary extension of this argument would mean, then, that churches should advocate regular physical exercise and maintaining a healthy diet with lots of fruit and vegetables. Many of the dietary and other rules of the Old Testament were designed to protect people’s health in the culture and environment of those times. In contemporary Western culture, the challenges to health are quite different. Hence, there are different implications of the ancient principles of taking care of our physical and mental wellbeing as we are able.

Philip Hughes

References:

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2014) Australia’s Health 2014, Canberra: Australian Government.

Kaldor, Peter, Philip Hughes and Alan Black (2010) Spirit Matters: How Making Sense of Life Affects Wellbeing, Melbourne: Mosaic Press.

Stark, Rodney (2012) America’s Blessings: How Religion Benefits Everyone, Including Atheists, West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press. References are to the e-book version.

World Health Organisation (2013) World Health Statistics 2013: A Wealth of Information on Global Public Health, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation.

Data:

Data from the International Social Survey Program (2011) on public health was downloaded from the issp.org. The computer file is ZA5800.sav.

This article was first published in Pointers: the Quarterly Bulletin of the Christian Research Association, Vol. 24, no.3, September 2014, pp. 1-6.