What do people mean when they identify themselves as Christians? The meaning varies, of course. Some mean that they are involved in Christian churches. In Australia, there are 10 million people who identify themselves as Christians but who rarely, if ever, attend a church. What do they mean by that identification? Do they ‘believe’, but choose ‘not to belong’? In other words, do they like Jesus, but dislike the churches? Or does their identification mean that, in some sense, they ‘belong’, even if they do not attend?

Rick Warren, the famous author and minister of Saddleback Church in the USA, is typical of many evangelists in assuming that there are many people who believe in God and are impressed with Jesus, but have not connected with a church. He refers to these people as ‘nominal Christians’: Christian in name but not associated with a church (see, for example, Warren 1995). Warren thinks, like many other people, that these people should be a major target for church mission and that the secret of success in mission is making the church appealing to such people, or to use Warren’s language, ‘more seeker friendly’. It is possible that Warren is correct about Americans, but is he correct about Australians and the British?

Nominalism

The issue became a significant one in the United Kingdom in 2001. For the first time, the Census contained a question about religion. Many people were surprised that 72 per cent of the population in the UK identified themselves as Christian (Day 2011, p.28). On the other hand, the International Social Survey program (2010) for Great Britain found that just 17 per cent of adults claimed to attend a church monthly or more often. While the extent of nominalism is not as great as some have claimed (Day 2011, p.178 claims monthly church attendance among the British is 7 per cent), more than 50 per cent of British people may be described as ‘nominal’. But before making judgements about nominal Christians, it is important to better understand them, and, in doing so, better understand the nature of ‘belief’ in our world. In the United Kingdom, Dr Abby Day, a senior research fellow at the University of Kent, has been exploring what people mean by belief and by their identity as Christians. Her book Believing in Belonging: Belief and Social Identity in the Modern World was published by Oxford University Press in 2011.

As noted above, it is often assumed that the church rather than faith is the barrier to church involvement. People ‘believe without belonging’, to use a phrase which emerged from the sociologist, Grace Davie, in 1994. More recently, Davie (2007) has suggested that many people believe ‘vicariously’ through others. They see church leaders as believing on their behalf.

Research Conducted by Abby Day

Day began her research by asking people what they believed in. Her sample was small: just 68 people (Day 2011, p.30), but the range extended from school students to the elderly, and included people from professional and working-class sectors of society. In her initial questions, Day avoided the word ‘religion’ or ‘Christian’, giving people an open opportunity to shape their responses.

Day noted several ways in which people responded to her question. The conditional responders who began by eliminating religion from the possible responses:

Nothing religious at all, anything like that. I believe in things like love and stuff like that, feelings, more so than religious things. I don’t have any beliefs on that side at all (Day 2011, p.41).

The stalling responders who bought time, like the book-keeper who responded,

Oh dear, that’s an interesting question to start with, isn’t it?

The assertive responders who were quick to assert their responses:

I believe in God and we do, we’ve not been to church so much recently, because I’m so busy, but we do go to church.

Day argues that many people are constructing what they are saying, reflexively, in some depth. (Day 2011, p.42). She goes on to say that she realised that many people were telling stories or ‘belief narratives’, often connected to personal values, trust and emotion, rather than to facts, propositions or creeds (Day 2011, pp.43-44).

In analysing the interviews, Day identified two belief orientations which she describes as anthropocentric and theocentric (Day 2011, p.156). The majority of people she interviewed were anthropocentric. Their beliefs revolved around their relationships with specific other people, most commonly partners, family and friends. They believed in treating these people morally: as they themselves would like to be treated. Day found a link between ‘morality and belief’ rather than between ‘morality and religion’. It was a matter of ‘doing the right thing to your family, your neighbours, your friends’ (Day 2011, p.131). Violence was generally seen as wrong. It was important to treat people fairly, properly, and equally, whatever their relative social status.

Whether religious or not, Day argued that most people shared a ‘social morality’ as nice, law-abiding, non-violent people. Those with an anthropocentric orientation often traced their moral heritage back to those personal relationships. For these people, says Day, ‘family is one of the most important sources of meaning, morality and even transcendence – all areas conventionally associated with religion’ (Day 2011, p.93). To a large extent, their beliefs could be described as ‘secular’ in as far as they rejected the idea of a creator or heaven. On the other hand, Day found that many of these people had some sort of belief in spirits and many described themselves as having had experiences of the presence of, or communicating with, past members of their families.

Day found that half of all those who had an anthropocentric orientation to belief said that, when asked to state their religion on the census, they responded that they were ‘Christian’. Day identified three reasons for that response: natal, ethnic and aspirational. A minority of interviewees were described by Day as theocentric. These people said that their most important relationship was with God, and described their morality in terms of doing what God wants. That overarching relationship with God gave them a sense of protection and meaning. Most of them believed they would one day be united with God in heaven.

Natal Reason

For many people being a Christian was associated with the story of their birth or their early up-bringing. Day cites a few examples of responses when people were asked what they had marked on the census form:

I probably would have put Christian, actually, because that’s how, what I was raised as. Not that I’m a practising one. But, I was born and raised that, so if I were to mark a religion that would be it.

How I was brought up. I don’t believe, but I don’t disbelieve either.

I suppose it was instilled into me from an early age that I was a Christian (Day 2011, p.55).

Christian. Don’t know why. Because I was baptized. I’d just answer Christian without thinking (Day

2011, p.56).

Day talked to a student, Jordan, who described himself as a Christian. Day asked him if he believed in God and Jesus, and Jordan responded that he did not, but his grandparents did. ‘They’re like Irish and really strong Christians’, said Jordan. ‘And so they believe in …?’ asked Day. ‘The whole Bible thing’, said Jordan. His own sense of being a Christian was embedded in his grandparents, Day reflected (Day 2011, p.79). Another young interviewee, a girl this time, also talked about her grandparents as she unpacked what she meant by identifying herself as Christian.

Ethnic or Cultural Reason

Sometimes interviewees made a link between morality and nationalism, Day argued. People spoke of being Christian because it described ‘the way people like us live’ in comparison to ‘ethnic others’. (Day 2011, p.138). Sometimes these people made references to unfairness in regards to immigrants or asylum seekers who were believed to be receiving more benefits than they were (Day 2011, p.139), identifying the immigrants as ‘not Christian’ compared to the Christian British people.

Day quotes from one couple who did not hold any Christian doctrinal beliefs or attend church, or think that religion was important in daily life, but had a strong sense of ‘being Christian’ because they were born into a Christian culture. One person explained his decision to put ‘Christian’ on the census in this way:

Well, only because they asked us, not because, we wouldn’t have any qualms, but that’s the British

way, isn’t it? If people are not religious, they’re C of E. Church of England. Weddings, funerals, and

christenings (Day 2011, p.189).

Day describes an older couple, Robert and May. They were not sure that God existed and they never went to church. However, they would describe themselves as Christian because they had ‘a Christian outlook’ (Day 2011, p.58). They went on to distinguish that outlook from that of Muslims arguing that ‘the women are trodden into the ground in the Muslim world’ (Day 2011, p.56).

Aspirational Reason

There were a few people who described themselves as Christian because they thought that Christians were respectable people, and, although they were not quite living up to that standard, that was how they wanted to live.

‘Christian’ as Belonging

The claim to be ‘Christian’ was not just an unthinking response, Day argues. Yet, for most of these people, it had nothing to do with either beliefs or involvement in a church. Most of those who described themselves as Christian in this way rejected even belief in God and were not interested in Jesus, contrary to the patterns described by Warren (Day 2011, p.171).

By identifying themselves as Christian, Day argues, her interviewees were indicating a sense of belonging to a particular ethnic, cultural or social group. Indeed, Day suggests that beliefs are often about that. They are not so much about providing meaning for the individual, but rather, they are pragmatic devices for describing a set of personal relationships and boundaries, she says (Day 2011, p.13).

Day does not examine the theocentric orientation at any great depth. However, she notes that the theocentric language described a different form of belonging: to a community or church, united by people who shared similar beliefs. Day noted that, to some extent, those who held anthropocentric and theocentric orientations tended to denigrate the sort of belonging they perceived in each other (Day 2011, p.169). Those who identified with church communities tended to blame the disregard of the church and of Christian teaching for the low levels of morality in British society. On the other hand, those who held an anthropocentric orientation tended to denigrate the reliance on God for morality as a weakness among church attenders, with some arguing that religions were immoral. Day commented that the way people regarded the beliefs of others tended to function in a way to strengthen their own sense of identity or community. To that extent, she said, ‘belief functions as an ideology, a way of promoting a certain view of ourselves, the world around us and most specifically how we want it to be’ (Day 2011, p.169).

Differences between Identity, Believing and Belonging in Australia and Britain

Day sees that one of the consequences of her research is that observers of society should dispense with ‘binary, subsidiary categories of belief’, such as religious or secular and focus on multidimensional, interdependent orientations (Day 2011, p.202). People are not simply religious or secular. On the other hand, it might be argued that her binary distinction between those with an anthropocentric and a theocentric approach to belief is also inappropriate. There are many varieties in between. People do not simply belong to Christianity ethnically or culturally, on the one hand, or to a Christian community on the other. There are many people who move between the two. In fact, many Australians and British people attend a church occasionally, especially at Christmas and Easter. Many people who do not attend a church affirm Christianity as the source of the basic values of love and care. In these ways, the anthropocentric and theocentric perspectives are not mutually exclusive and there are positions between them (Hughes 2011, p.16).

At the same time, there are many church attenders who would feel uncomfortable with the way Day describes the theocentric approach. There are many people who believe in God and are involved in a church, but do not think of God as involved in the intimate details of everyday life. Of adults who attend church in Australia, 72 per cent agree with the statement that God concerns Himself with human beings, but 28 per cent are not sure, disagreed, said they could not choose, or chose not to answer the question. Day’s description of the theocentric approach accords with the conversionist and devotionalist patterns of faith which stress access to a personal God (Hughes and Blombery 1990).

Day’s description does not accord with the conventionalist and principlist patterns of faith which place the emphasis on Christian values (Hughes and Blombery 1990). These people see God as the creator and sustainer of the universe who has established the physical and moral rules by which the universe operates. Worship involves the acknowledgement of God rather than seeking God’s intervention in daily life. However, the idea of an intimate personal relationship with God does not always coexist comfortably with such a vision of God.

There are some significant differences between the Australian and British contexts which has an impact on how belonging, believing and identity operate. The first is the fact that the Church of England is an established church in Britain and this provides a basis for the identification of Britain as Christian. There is no established church in Australia.

Nevertheless, there are some Australians who believe that Australia was founded by the first settlers from Britain as a Christian country and Australia should continue to be seen as a Christian country. It is noteworthy that lobby groups such as the Australian Christian Lobby state on their website that 12.7 million or 64 per cent of Australians declared themselves as Christians in the 2006 ABS Census as if that gives justification to their political voice.

It should be noted that the British Census asked people if they were Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, Moslem, Jewish and so on. It did not ask, as does the Australian Census, for their denomination or religion.

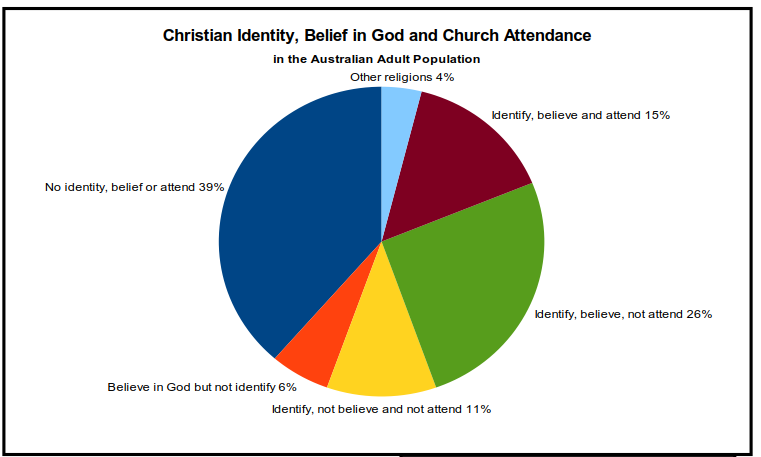

While Day is right in holding that surveys hide a great range of rich information, survey data can provide a very rough test of the relevance of Day’s observations to the Australian scene. As shown in Figure 1, about 11 per cent of the Australian population identify themselves as Christian but do not believe in a personal God and do not attend a church, and thus would probably fall into the Christian anthropocentric category that Day identified. They identify with a Christian denomination, but they do not believe in God and do not attend a church.

However, there are two other groups in the Australian population which do not fit Day’s thesis quite as easily. The first and larger of these two groups is the 26 per cent of the population who identify as Christian, who say they believe in a personal God, but who do not attend a church monthly or more often. One cannot determine whether Day would identify these people as having an anthropocentric or theocentric approach to belief, but the expression of belief in God and the fact that some of these people pray suggests that there is a theocentric dimension to their approach to life, even though they do not belong to a church. Without analysing these people in depth, it would seem that many of them sit more easily with Davie’s description of ‘believing without belonging’.

The second group is a smaller one: 6 per cent of the Australian adult population who say they believe in God but do not identify with a Christian denomination or other religion. Some of these people may have an anthropocentric perspective even though they are willing to tick a box to say that God exists on a survey. Ticking such a box does not mean that belief in God has a high level of significance for them in daily life. Nevertheless, it is possible that some of these people may have a theocentric orientation, but for various reasons choose not to identify with a Christian denomination.

The ‘ethnic reason’ for Christian identification that Day identifies makes a lot of sense in the Australian context. Indeed, it has further ramifications in Australia because the large majority of Australians arrived here as immigrants within the last two hundred years and because many people have some sense of connection to previous homelands and ethnicities. This sense of ethnicity may well have been heightened by the high level of multiculturalism in Australia. For many people, one of the associations with ethnicity is religion. Hence, religious identification can be a significant carrier for belonging to a particular ethnic group within a multi-ethnic society. There are many Catholics for whom their Catholic religion is associated with an ethnic heritage: Irish, Italian, Polish, Vietnamese, or Filipino, for example. For other Vietnamese, Buddhism is associated with their sense of being Vietnamese. Greeks identify with the Greek Orthodox Church. The Lebanese community in Australia is divided between those who have a Christian heritage expressed through the Antiochian Orthodox Church, the Maronite Catholic Church or through Islam. But the ‘ethnic’ sense of belonging is not there only among those who do not attend church. For many people, churches provide a significant way in which ethnic communities gather and language and values are reinforced (Bouma 1997, pp.74-75). While Day did not identify anyone with a theocentric perspective who spoke of their religious identification in ethnic terms, there would be many such people in Australia.

On the other hand, I see little evidence in Australia for the ‘aspirational reason’ that Day discusses. Indeed, Day’s own evidence for this reason is weak. Certainly she quotes interviewees who noted people they aspired to emulate who were Christian, but Day does not show conclusively that, that aspiration was the reason for their own identification as Christian. The lack of a strong sense of social class or the idea of a ‘proper Australian’ and the lack of visible connections between social class and religion mean that this type of nominalism plays little role in Australian society.

Day’s point that religious belief statements are a means whereby people indicate a sense of belonging does make much sense. In Australia, belief statements are commonly used to indicate belonging to a particular religious sub-group. For example, the person who says ‘I believe in the Bible’ is often locating him or herself as belonging to an evangelical or charismatic Christian denomination.

It is not primarily a statement that every part of the Bible must be taken at face-value, although at a secondary level, it may mean identification with Christian denominations who generally take the miracles at face-value. It does not mean that they take every law in Leviticus as moral instruction, although it may mean identification with Christian denominations which are opposed to homosexuality. At the same time, the statement ‘I believe in the Bible’ is often used to disassociate a person from other Christian groups which have more liberal views both of miracles and of morality. Such statements of belonging are used by those who attend a church and those who do not. Another element which is largely missing from the British scene but which is important in Australia is the impact of religious schooling. The presence of church-related schools is much greater in Australia than either Britain or the USA or most European countries. Sometimes statements of identification in a Census or survey, or belief statements, may be associated with the denominational affiliation of the school one went to. The extent of that influence has never been measured.

Day’s research points to the need to take seriously the identifications that people make and to see in

them the functions of the demarcation of belonging. Her assertion that statements of belief are primarily about belonging, rather than indicating a propositional or doctrinal commitment, is worthy of reflection. Day reminds those people in the churches that even among those people who identify themselves as Christian, the problem may not only be the church, a problem to be solved by ‘seeker friendly’ services. Many people have a sense of belonging to a Christian culture, ethnicity or heritage, for whom the beliefs about God and Jesus are problematic and who can make little sense of a theocentric perspective on life. But nominalism will not be resolved by arguing for the truth of such beliefs such as God and the resurrection. For many, belief is primarily a statement of belonging. However the details of this sense of belonging in Australia are likely to be a little different from that sense of belonging in Britain and exploring that sense of belonging in Australia needs further research.

Philip Hughes

References

Bouma, G. (editor) (1996) Many Religions, All Australian: Religious Settlement, Identity and Cultural Diversity, Melbourne: Christian Research Association.

Davie, G. (1994) Religion in Britain since 1945: believing without belonging, Oxford: Blackwell.

Davie, G. (2007) ‘Vicarious religion: A methodological challenge’ in N.T. Ammerman (editor) Everyday religion: observing modern religious lives, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Day, Abby (2011) Believing in Belonging: Belief and Social Identity in the Modern World, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hughes, P. and ‘T. Blombery, (1990) Patterns of Faith in Australian Churches: Report from the Combined Churches Survey for Faith and Mission, Hawthorn: Christian Research Association.

Hughes, P. (2011) ‘Access and Values: Functions of Religion in Australian Society’, Pointers, Vol. 21,

no.3. September.

Warren, R. (1995) The Purpose Driven Church: Growth Without Compromising Your Message and

Mission, New York: Harper Collins Publishing.

This article was first published in Pointers: the Quarterly Bulletin of the Christian Research Association, Vol.24, No.1, March 2014, pp.1-6.