The lyrics of Australia’s national anthem reflect the environmental uniqueness of this country. With phrases such as “golden soil”, “nature’s gifts”, “beauty rich and rare”, arguably many Australians would consider the anthem as reflecting their own views of the Australian environment. While many Australian Christians consider it a responsibility to look after ‘God’s environment’, there are other Christians who take literally the Genesis 1:27 suggestion that human beings should rule over all the world and are unwilling to take action to protect the environment (see Hughes, 1997).

Concern for the Environment

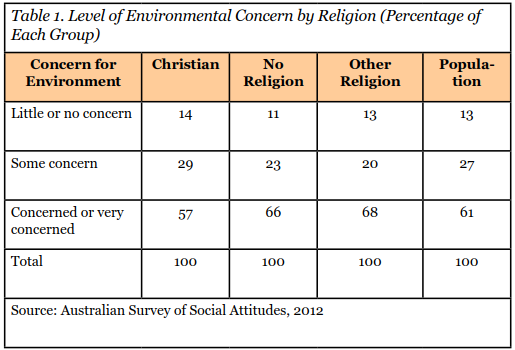

When participants in the 2012 Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (ASSA) were asked their level of concern about environmental issues,

• 13 per cent said they had little or no concern,

• 27 per cent had some concern, and,

• 61 per cent were concerned or very concerned.

Those from non-Christian religions and those who said they had no religion were the most concerned about the environment, with around two-thirds of people in each group stating they were concerned or very concerned. Christians showed the least concern about environmental issues.

However, while overall the level of environmental concern amongst Christians was lower, levels of concern varied slightly between denominations. Orthodox Christians were most concerned (62 per cent concerned or very concerned), although they also had a high proportion of people who had little concern (22%). Sixty per cent of Catholics were concerned or very concerned. Pentecostal Christians were least concerned (53%).

There was no significant difference between the environmental concern of non-church attenders and those who attended religious services occasionally or frequently.

Most Important Environmental Problems

According to the survey, Australians considered that the most important environmental problems for society as a whole are water shortage (29% consider it most important), using up natural resources (21%) and climate change (17%). A further nine per cent of Australians considered that chemicals and pesticides are the most important problem, while five per cent of Australians each considered that genetically modified foods, water pollution, air pollution and domestic waste disposal is most important. Four per cent of Australians thought nuclear waste is the most important problem.

Of note is that although Christians and non-Christians agreed on the shortage of water being the most important, the proportion of Christians who considered climate change important (13%) was considerably lower than those of other religions (23%) and those who had no religion (24%). A greater proportion of people with higher levels of education (degree or higher) rated climate change important (25%) compared to those with a high school level of education (11%).

When respondents were then asked to consider the environmental problems that most affected them and their families, there was much more diversity in the answers than in the previous question. Again, water shortage was considered the most important problem, with 17 per cent choosing that response. Chemicals and pesticides (13%), climate change (12%) and genetically modified foods (12%) were the next most popular responses. Domestic waste disposal, air pollution and using up the natural resources were each considered most important by ten per cent of Australians. Water pollution (5%) and nuclear waste (1%) were ranked at the bottom. There was no significant difference between the different religious groups.

Interestingly, twelve per cent of Australians did not consider any of the listed options as the most important environmental problem for them. However, the structure of the question makes it unclear whether those individuals considered other problems more important than those listed, or whether they considered they were not affected by environmental problems at all.

Causes and Solutions

When asked to consider how much they knew about the causes of the environmental problems that affected their family and society, most Australians considered that they had at least some knowledge of the issues. On a scale of one to five (where one indicates “know nothing at all”, and five indicates “know a great deal”), 44 per cent said they have an average understanding (scoring themselves a three out of five), while 30 per cent said they knew a fair amount, and ten per cent said they knew a great deal. Around 16 per cent admitted to not knowing much about the problems or knowing nothing at all.

Fewer Australians admitted to knowing about solutions to the environmental problems, with 20 per cent stating they knew a fair amount and five per cent stating they knew a great deal. Around 44 per cent had an average knowledge of the issues, 24 per cent said they do not know much, and seven per cent admitted to not knowing anything at all.

Similar proportions of Christians and people of other religions stated they have some understanding of the causes to the environmental problems (37%), while a higher proportion (45%) of people of ‘no religion’ considered they knew something or a great deal about it.

Willingness to Make Sacrifices to Protect the Environment

Only a small proportion (7%) of Australians indicated that they were very willing to pay much higher prices in order to protect the environment. A further one-third said they were fairly willing, while 21 per cent were fairly unwilling, and 16 per cent very unwilling. Another 24 per cent were neither willing nor unwilling.

Fewer people were willing to pay much higher taxes to protect the environment. Twenty-nine per cent of Australians said they were either fairly or very willing to pay higher taxes, while 21 per cent were unsure, and 50 per cent said they were not willing. Just under one-third of Australians (32%) were willing to accept cuts to their standard of living in order to protect the environment, while 23 per cent were unsure, and 46 per cent were fairly or very unwilling to do so.

In comparison to people of other religions and people of no religion, Christians were the least willing to pay much higher prices (35 per cent were willing), least willing to pay much higher taxes (23%) and least willing to accept cuts to their standard of living (28%) for the sake of the environment.

To understand why people do or do not make sacrifices to protect the environment, respondents were asked to consider various statements. Sixty-two per cent of Australians disagreed to some extent that it is too difficult to do much about the environment, while a similar proportion (60%) stated that they generally do what is right, even if it costs money or takes time.

Just under one-fifth (19%) of Australians believed there are more important things to do in life than protect the environment. One-third believed that it is more than just an individual effort and that there is no point in doing things to care for the environment unless others do the same. Christians were most in agreement with this view (38%), compared to non-Christians (31%) and people of no religion (24%).

Significant differences existed between religious groups over whether claims about environmental threats were exaggerated or not. Overall, 46 per cent of Christians agreed with the statement to some extent, compared to 32 per cent of non-Christians and 30 per cent of people of no religion. Geographical location was also a significant indicator: the further away from a major city the respondent lived, the higher the propensity to agree with claims about environmental exaggeration. For example, one-third of people who lived in the inner metropolitan area of a big city agreed, in comparison to 51 per cent of those who lived in a rural area.

Australians were divided as to whether environmental problems have an effect on their everyday lives, with 38 per cent believing they did, 30 per cent unsure, and 32 per cent believing they did not.

Efforts for the Sake of the Environment

The 2012 Australian Survey of Social Attitudes also asked people about what efforts they went to for the sake of the environment. The vast majority of Australians (94%) said they always or often made a special effort to sort various materials for recycling. Just over half of the population (52%) said they always or often reduced energy or fuel use at home, while the same proportion said they always or often chose to save or re-use water for environmental reasons. Some had chosen to avoid buying certain products (43%), while others had made an effort to buy fruit and vegetables grown without chemicals (41%). Just under one quarter (23%) had cut back on driving for the sake of the environment. There were no significant differences between the actions of Christians and those of other religions or of no religion.

Some Australians said they were members of environmental protection groups, although the proportion was relatively small at around eight per cent. Significantly, Christians were least active in these groups (five per cent were involved) compared to those of other religions and of no religion (both 12 per cent). Those who lived in country or rural areas were the most involved in such groups (13%).

In the previous five years, 29 per cent of the population had signed a petition about environmental issues, while just under one-quarter (24%) had given money to an environmental group. Five per cent of the population had taken part in a protest or demonstration about an environmental issue within the previous five years.

While many people considered that they take action for the sake of protecting the environment, the financial cost savings of recycling no doubt also play a role. For example, many households would conserve electricity not just to lessen the burden on the environment, but because they know they will pay less in their next energy bill. It is somewhat easier to make a concerted effort for the sake of the environment if there are associated cost savings. Additionally, many local councils now have advanced recycling practices in place so that it is just as easy for households to recycle many waste products as it is to send them to landfill.

Best Approaches to Protecting the Environment

According to the survey, many people thought that Australia is playing a positive role in what it does to protect the world environment. Thirty per cent of Australians considered that we are doing more than enough in this regard, while 40 per cent thought that we are doing about the right amount. The remaining 30 per cent thought that we are not doing enough. Christians were most positive about the role Australia was playing in protecting the environment: three-quarters considered that the country is doing about the right amount or more than enough. Sixty per cent of non-Christians considered that the country was playing a positive role.

In deciding who had the main role in protecting the environment, 28 per cent of people thought that ordinary Australians should decide for themselves what they should do, even if it meant not always doing the right thing. Just under half (48%) thought that the government should pass laws to make ordinary people protect the environment, even if it interferes with people’s rights to make their own decisions. Twenty-three per cent of Australians could not decide.

In regards to the role of industry, three-quarters of Australians thought that the government should pass laws to ensure businesses protect the environment, while 12 per cent considered that businesses should decide for themselves what to do, even if it meant they did not always get it right. A further 13 per cent could not decide.

Australians think that the best way to get business and industry to protect the environment is to use the tax system to reward them when they do so – 41 per cent considered this the best approach. Two alternative approaches – heavy fines for failure to protect the environment, or more information and educative measures about the advantages – were each considered the best methods by 28 per cent of the population.In getting people and their families to protect the environment, 47 per cent of Australians thought that education and information was the best approach, while 35 per cent considered that using the tax system as a reward was the best method. Fourteen per cent considered heavy fines as the best approach for those who damaged the environment.

Future Energy Needs

In considering the country’s future energy needs, two-thirds of Australians said priority should be given to the more environmentally-friendly options of solar, wind or water power. Smaller proportions of the population said priority should be given to coal, oil or natural gas (13%), nuclear power (13%), and fuels made from crops (6%).

Of significance is that Christians were the least in favour of solar, wind and water power (62%), in comparison to non-Christians (74%). Males (60%) were also significantly less favourable than females (72%), and were much more inclined (20%) to give priority to nuclear power than females (7%).

Attitudes to Science

Survey respondents were asked their views on science, firstly, if they agreed or disagreed that “We believe too often in science, and not enough in feelings and faith”. Almost one-third of the population agreed or strongly agreed with that statement. However, people of different religious groups had differing views, ranging from 18 per cent of those who said they had no religion, to 71 per cent of Pentecostals affirming the statement. Of all the Christian denominations, the Orthodox and the Anglicans were the least likely to affirm the statement. There were also significant differences among church attenders and those who did not attend, with 55 per cent of regular attenders (attending monthly or more often) affirming the statement, compared with one-quarter of those who never attended.

On the other hand, when asked if “Modern science has done more harm than good”, there were fewer differences – although still significant – between the religious groups. Catholics and Anglicans were least likely to affirm that statement (14%), while the Pentecostals were most likely to affirm it (28%).

Overall, there was no difference between religious groups when asked if “Modern science will solve Australia’s environmental problems without major changes to our way of life”, with 21 per cent affirming that statement, 27 per cent unsure and 52 per cent disagreeing or disagreeing strongly.

Science and Concern for the Environment

Analysis of the data showed that trust in science was an important component in concern for the environment. In other words, the more positive the view of science, the stronger the concern for the environment. The next strongest positive predictor of concern for the environment was whether the respondent was female, while the strongest negative predictor was whether the respondent said they were Christian. An important point here, however, is that frequency of church attendance was not a significant predictor at all in concern for the environment. So, it is not active involvement in a church community that predicts positive or negative levels of environmental concern, but rather identification with a Christian denomination.

Age and educational levels were not strong predictors of concern for the environment. On the other hand, perhaps predictably, those with higher levels of education responded much more negatively to the view that we believe too often in science and not enough in faith and feelings, and also to the view that modern science does more harm than good. Identifying with a Christian denomination and attending church regularly were strong predictors of a positive response to both of those statements.

Conclusions

The Christian Research Association’s research paper on values and religion among Australians (Hughes, 1997) showed that Christian beliefs play a part in people’s attitudes towards the environment, and that input from religious leaders and thinkers could well have a significant impact (Hughes, 1997, 24). Results from the 2012 Australian Survey of Social Attitudes show Christians and non-Christians share similar views on some environmental issues, but have markedly different views about others.

Christians in general were more sceptical about science compared to non-Christians, although people of some Christian denominations were even more sceptical than others. This was a major reason, but not the only one, for their lower levels of environmental concern. In comparison to non-attenders and occasional attenders, regular church attenders held greater negative attitudes to science.

Christians rated climate change significantly lower than other Australians as an important issue for society. However, when environmental problems were localised to the personal or family level, Christians and non-Christians shared similar views about the most important issues.

Christians and non-Christians were just as likely to make adjustments to their everyday lives for the sake of the environment, such as by recycling household waste or reducing energy in their homes. However, Christians were less willing to pay higher prices, pay higher taxes or accept cuts to their standard of living than others in the general population.

There are many positive environmental initiatives happening in local churches, and some denominations are quite active in promoting those and other initiatives (i.e. Catholic Earthcare, UnitingJustice Environmental Statements, Anglican EcoCare Journal). Additionally, a significant majority of Christians – across many denominations – are very concerned about environmental issues. On the other hand, some Christians show little concern about environmental issues facing society, and show even less concern about taking steps to make changes.

If Australian Christians understand God as creator, and human beings as having responsibility for the care of creation, then Christians should be at the forefront of positive environmental endeavours. Promoting and living a lifestyle that ensures a sustainable future for the environment should not just be a worthy societal value, but rather an implication of the Biblical injunction to care for creation and for all people, including those of future generations.

Stephen Reid

References

Hughes, P. 1997. ‘Values and Religion: A Case Study of Environmental Concern and Christian Beliefs and

Practices among Australians’, Research Paper No. 3, Christian Research Association.

Data source: Evans, A. 2012. Australian Survey of Social Attitudes, The Australian National University: Australian Demographic & Social Research Institute.

This article was first published in Pointers: the Quarterly Bulletin of the Christian Research Association, Vol. 24, no.3, September, 2014. pp. 11-16.