It has been widely reported that the proportion of Australians who identified as Christians in the Census diminished from 52 per cent in 2016 to 44 per cent in 2021. This is, indeed, a significant change. It represents a reduction in actual numbers of people identifying themselves with a Christian denomination by a little over one million in 5 years, a reduction of nine per cent on the number in 2016. It represents a continuation of the trends towards decreasing proportions of Christians in Australia since 1966. However, it means that the rate of change is increasing: the number of Christians in Australia is dropping quicker than ever.

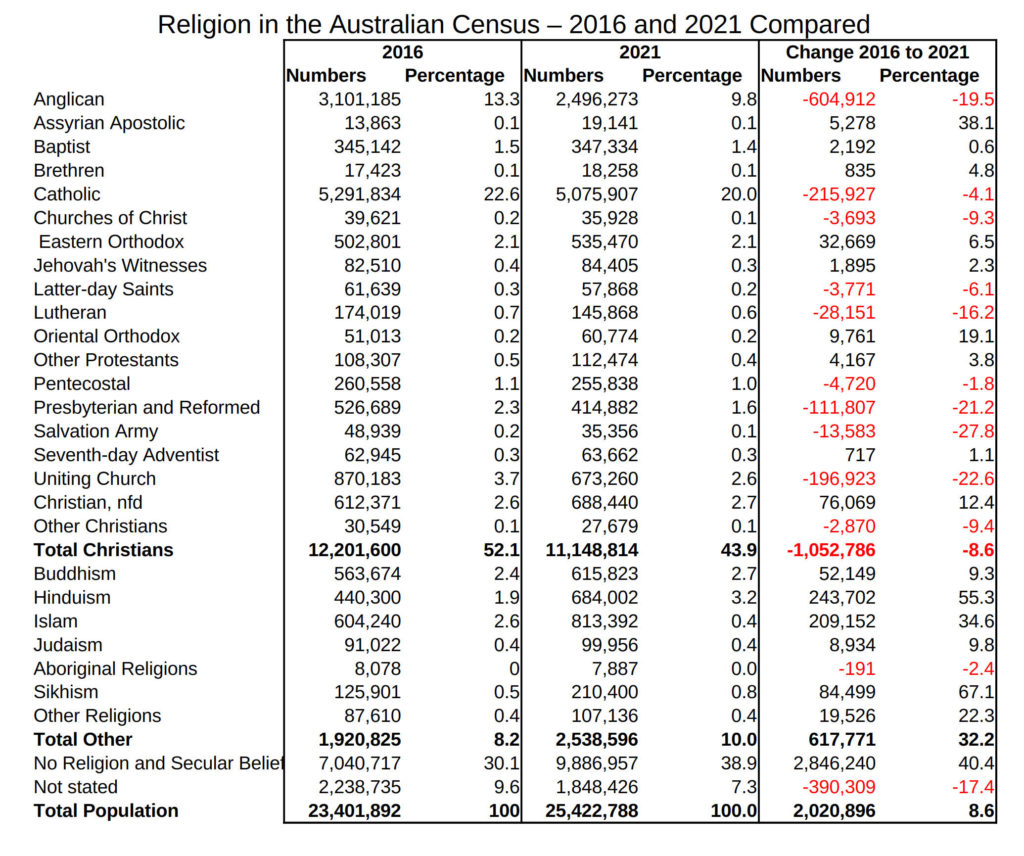

This general picture hides some variation in different denominations as shown in the following table.

The fastest rate of decline in numbers (28%) was in The Salvation Army, followed by the Uniting Church (23%), the Presbyterians and Reformed (21%), Anglicans (20%), and Lutherans (16%). There was a slower rate of decline in numbers among the Churches of Christ (9%), Latter-day Saints (6%), and Catholics (4%) and Pentecostals (2%). The result regarding the Pentecostals shows that the recent growth of Pentecostals has not only come to an end, but has reversed. Not only are the Pentecostals not keeping up with the growth of the population, but they are actually losing people in absolute numbers for the first time in more than 100 years.

There was a small increase of numbers, but a fall in percentage in the population, among the Baptists, the Brethren, the Eastern Orthodox, the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the Seventh-day Adventists. These groups did not lose numbers, but did not keep up with the growth in the population.

There were two Christian groups which grew faster than the population: the Assyrian Apostolics and Oriental Orthodox. The Oriental Orthodox include the Coptic Orthodox from Egypt. They have grown partly from continued immigration from Egypt and other nations in the Middle East, but also because many of the immigrants who have come in recent decades have been having children.

One other Christian group has grown faster than the population: those who have written ‘Christian’ in the Census, rather than identifying with a specific denomination. Those numbers of ‘Christian, not further defined’ grew by 12 per cent compared with a population growth of nine per cent. This increase represents a couple of trends. Firstly, there are more people who do not wish to identify with a particular denomination, and some of these people may not want to identify with institutional forms of Christianity at all. Secondly, there are some people who prefer to identify themselves as Christians rather than identify with the specific church they attend. Indeed, it is likely that there are quite a few people who attend Pentecostal churches or independent churches or house churches who simply wrote ‘Christian’ on the Census form.

Some of the other religions, such as the Buddhists and Jews, grew at about the same rate as population growth (nine per cent and ten per cent respectively). On the other hand, there was much more rapid growth from the Muslims (35% growth), Hindus (55%) and Sikhs (67%). A large part of this growth has been the result of immigration between 2016 and 2021. India has been the major source of immigrants, including most of the Hindus and Sikhs, during those years. Other immigrants have come from Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan, and other Islamic nations. However, the growth is also due to the fact that many immigrants have come from these countries in recent decades and have had children in the past five years. The future growth in these religions is dependent on future immigrant trends.

While immigration has led to the growth of these other religions, many immigrants, even from such places as India, are Christian. Christian immigrants have continued to reduce the decline in some Christian denominations, such as the Catholics and the Pentecostals.

Among the greatest change in the responses to the religion question in the Census was the increase in the proportion of Australians indicating they had ‘no religion’. Nearly 10 million Australians described themselves that way, an increase of nearly three million compared with 2016, an increase of 40 per cent. ‘No religion means many different things to Australians. However, most fundamentally, it means that they do not want to identify with any particular religious institution. For many Australians, religion is simply off their radar and not something they think about. Other surveys indicate that many Australians are not at all sure about the existence of God, although many still describe themselves as ‘spiritual’. What the Census does not tell us is how these Australians find a sense of meaning.

We look forward to further releases of Census data so that the analysis can be continued.

In late July, CRA is hosting a free online seminar to unpack further the 2021 Census data. Please email admin@cra.org.au for further details of connection details.

Philip Hughes (Prof)